- Home

- Sara-Jayne King

Killing Karoline Page 3

Killing Karoline Read online

Page 3

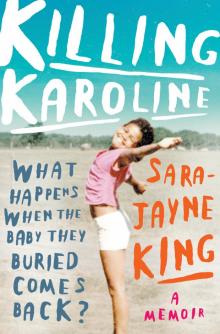

The final part of their plan had been devised even prior to leaving for England. They would do what to most people is the unthinkable, the unconscionable, the unspeakable. They would ‘kill Karoline’. They would say I had died.

Once back in South Africa, Kris and Ken tried, ultimately unsuccessfully, to put the past behind them and save their marriage. Ken maintains that by the time they arrived back from England, Jackson had ‘disappeared’. Kris would later tell me that she never again spoke to him after she returned to South Africa. Some inconsistencies in a letter she sent me years later led me to have my doubts about the truth and I once tried to imagine what conversation could have taken place between Kris and Jackson when she arrived back.

There is purple everywhere. Flecks of mauve, violet and amethyst dust settle on everything, like confetti, but there is nothing to celebrate. A stray lilac petal lands at her feet like a silent, fallen bell.

‘Jacarandas,’ she says to no one in particular as she crosses the courtyard, past two thatched rondavels. As she walks, she twists the ring on the fourth finger of her left hand. It is too big now and turns easily on her soft, white skin.

Down behind the kitchen, past the bins, and the rats, he lies in his room. Four solid brick walls. His uniform, a chef’s jacket, hangs idly on a broom propped against the door. The jacket is spotless, almost too white.

She calls out for him.

‘Jackie?’ Then, ‘Jackson?’

He rises cautiously, but respectfully to his feet and stands in the doorway.

‘Ma’am.’ She flinches at the formality. ‘You have come back.’

She nods and stutters weakly, ‘The baby … The baby, she—’

He interrupts.

‘They told me. I am so sorry for your loss, ma’am – and your husband’s too. It is not God’s plan for the mother and father to outlive the children.’

‘Jackie…’ She starts to move towards him, but his eyes tell her he is no longer Jackie.

To this day it remains unclear as to whether my biological parents’ union was propelled by love or lust, rebellion or revenge, boredom or loneliness, fear or fun, or perhaps a combination of all of these. I still do not know. So much remains hidden, left unsaid, buried and locked away by those who do know but, for reasons known only to them (I assume guilt and shame), they chose not to divulge. When I think about my story, it often feels like a play. A tragedy, of course. Akin to Macbeth, the one whose name shall never be spoken. There is a script, but none of the players is true to it. Instead they ad lib, casting aside what is written to show their own character in their best light. Lines are discarded, scenes deleted, characters so altered from the original that by the end the true story is lost. Whatever the real circumstances of how I came to be born into a system of segregation, hate and oppression, the ramifications would, like a ten-tonne weight tossed into a pond, ripple outwards for times and times and times to come.

CHAPTER 4

Sarah Jane is adopted

* * *

My adoptive parents were never really meant to have been my mother and father. It’s an unpopular opinion, usually among APs (adoptive parents) and well-meaning social workers who want the adoption machine to keep turning and churning out rainbow families. They forget that at the start and the heart of every adoption story is pain. I wasn’t orphaned, I had two parents (three if you counted Ken), but I was just unwanted. As I say, it’s an unpopular opinion among non-adoptees, many of whom would rather hold on to the idealistic view that adopted children are somehow born for the sole purpose of becoming part of their adoptive families. Some even go further, suggesting that the universe or, more difficult for me still, ‘God’ has pre-ordained the adopted child’s place in their ‘new’ family. But, for me and many other adoptees I have come to know over the years, this is really just an attempt at sugaring a very large, very bitter, very white pill. Because, in its basest form, adoption is a social construct, designed to kill three unfortunate birds with one stone. It is not what nature intended; in fact, it goes completely against the natural order of things.

I came to be my adoptive parents’ child not because of some altruistic motivation on their part to step in and rescue an unwanted child, but because, devastatingly for them, they were unable to have their own children. If I were a believer in such things I might conclude that their infertility was a sign that perhaps theirs was a life in which children were not destined to be a part. My take on this is not a popular consensus.

In 1971, my mum Angela, a liberal conservative from a privileged and proper, upper-middle-class family in the heart of England’s home counties, marries my father Malcolm. She is thirty-one. Old for the time. Her parents, my grandparents, both come from well-off backgrounds, and my maternal grandmother’s family was certainly considered very wealthy. My great-grandfather works ‘in the City’ and amasses something of a fortune, affording him such luxuries as a Rolls Royce, a personal driver and live-in housekeeper, and even a family trip to New York, which my grandmother records in her diary at the time: ‘We visited a nightspot on the island of Manhattan this evening and watched the negroes jive dancing to a very up-tempo jazz band.’

My mother and her younger brother, Jonathan, both attend private schools, travel abroad when it is uncommon to do so and receive considerable financial assistance from my grandparents for cars, weddings and, later, property.

I am close to my maternal grandparents, Granny and Grandpa. More so my grandmother, who is as grandmothers are in storybooks: white, plump, grey-haired and ample-bosomed. Granny – or Madge, as she is known to her friends, Madeline officially – teaches me how to make rock cakes, and is excellent at tucking me in at night, pulling the duvet and blankets right up around my chin and then folding it in at the sides so that I’m cocooned in cotton.

She is proper to the extreme and refers to the loo as the ‘lavatory’ (never the ‘toilet’), and is well into her eighties (and me my late teens) the first time I see her out of a skirt and wearing a pair of trousers. When she answers the door in her new ‘pants’, I start for a second, unable to recognise her.

When my playing is good enough, Granny and I play duets on the piano, and when I stay the night with her and Grandpa we read aloud from Peter Rabbit and Swallows and Amazons. Despite her propriety, Granny is a hoot, and very frank. When I am nine we howl with laughter at the rude bits in A Fish Called Wanda and when, as a curious twelve-year-old, I ask her, ‘How many times do you think you and Grandpa had sex?’, she tilts her head, considers and says simply, ‘Thousands, darling.’

One day, when I am eight, we watch the summer Olympics taking place in Seoul. As their generation commands, Granny and Grandpa are patriotic, so we have been glued to the athletics for over an hour. The presenter announces the next event, in which a man named Peter Elliott is running the 1500 metres for Great Britain. As Elliott and the rest of the competitors (including a black runner from Kenya) crouch at the starting line, Granny turns to me and says, ‘I’ll cheer for Britain, you cheer for Africa.’ For a reason I do not understand at the time, I am hit by a feeling of loss and also panic. It’s the same feeling I get when I lose sight of Mummy in the supermarket. For the next three minutes I watch the thin, black man hurtle around the track, my fingers crossed in my lap willing him to lose. He pips Elliott by less than a second, and at the same time manages, by a toe, to create a further irreversible separation between me and the family I think are mine.

There is never a doubt in my mind that Granny loves us. Me especially; Adam is more difficult because he is often naughty, but because I am mostly good and smart and easy (I exhaust myself to achieve this), I am definitely loved. I think my cousins, my uncle’s two daughters, several years older than us, are loved more, but understandably. They are proper grandchildren and look like Grandpa. Adam and I are denied full, peak membership to our family because we don’t have the ‘family nose’.

Grandpa John is even better than a storybook Grandpa because rather than smoking a

traditional pipe, he is always sucking on a special machine that makes a chugga-chugga whirring noise. He has to do it for his lungs. When he breathes in through the mouthpiece, his whole chest heaves, and the braces that he always wears attached to his trousers look as if they will ping right off his body. Because of his bad lungs he didn’t have to go to the war and could stay away from the battlefield, instead growing vegetables in his nursery. Grandpa teaches us and our friends how to gamble using coloured counters, and we are masters at Black Jack before we are in middle school. He loves us too, but in a less tactile way than Granny. I remember hugging him only once in my life, before bed one night, and it felt strange – for both of us, I think – and I never did it again.

One of my lasting memories of Grandpa is of him in hospital a few months before he died. The hospital was close to my school and I had been told to walk there and meet my mum instead of catching the school bus home.

When I walk into his private ward, weighed down by my school satchel, Grandpa is having his blood pressure taken. A nurse I’ve never seen before turns to look at me, as I plop down into the plastic orange NHS chair by the bed. ‘This is my adopted granddaughter,’ Grandpa tells the nurse. He says it very matter-of-factly. The nurse keeps staring and then half laughs, awkwardly. I feel alien and confused sitting on that too-high chair, because even though I am adopted, I have never considered myself to be the ‘adopted granddaughter’. I don’t think of John and Madge as my ‘adopted grandparents’; they’re just Granny and Grandpa. But suddenly I am ‘other’. Other than what I’ve believed myself to be. Different. Separate. Not ‘real’. Real granddaughters, like my uncle’s children, are obviously better. They don’t need explaining.

I find it further destabilising when people ask if Adam is my real brother. I know what they’re asking, but it feels like they’re implying he may not be genuine. That he’s an imposter. That a real brother is out there somewhere and Adam’s just filling in. To me he’s as real as can be. When he punches me, it hurts and when he wins a race on sports day, I cheer the loudest.

People talk about my adopted mum and dad, or worse, refer to them as my foster parents. When they do, it’s like they’re saying my role as ‘daughter’ is temporary, uncertain, non-permanent. I know all about foster parents. They let you go. They have no obligations. I know this because Mum is a social worker and sometimes has to take unwanted children to their new foster homes in our car. One little boy, Connor (who is black like us) I meet a few times over the years as he moves from family to family, each time carrying his belongings in a black bin liner. I often wonder what is wrong with Connor. Why does no one want him? What is it that he does wrong at all these foster homes? One thing I know is that I’m certainly not a bin-bag child. I have a chest of drawers for my clothes and my own hand-me-down travel case with a tarnished bronze lock that doesn’t close properly.

Of all the things that grate me, the worst is when Kris is referred to as my ‘real’ or ‘natural’ mother. I am always puzzled how a woman who relinquishes her child in the manner in which mine did can be bestowed such a title. The various terms used by the well meaning and the ignorant disturb me greatly and, as a child, it is troubling to learn that there are such things as ‘real’ and ‘unreal’ family members. For a long time, though, I steel myself and fall in line with the language other people feel comfortable with or feel entitled to use when discussing my curious family. My voice is still too quiet to be heard over the din of other people’s needs.

My father, Malcolm, a few months younger than my mum, was born in Sheffield, Yorkshire, in 1940, the son of Arthur Kirk, a coal miner, and Maggie (Margaret) – or Yorkshire Granny, as we called her – a housekeeper. They met when Maggie went to work for Arthur. A widow with an infant child (my father’s half-brother Albert), Maggie went onto marry Arthur and, in doing so, inherited thirteen stepchildren, several of whom were older than she was. When she was forty and Arthur sixty, my father was born. I never once heard my dad speak about his father. I have no memories of my paternal grandmother and only one of ever going to Sheffield, where my father had grown up. It was for Albert’s funeral, and I was about eight or nine. The three-and-a-half hour journey up the M1 was interminable, and the stench of home-made egg sandwiches (my parents were frugal enough not to believe in over-priced road-side café fare) made my car sickness worse than usual. We stayed with an old friend of my father who had a tiny house in a tiny village on the outskirts of the town. We all had to share a bedroom and, despite being covered in a thick, rough blanket and being crammed into a small put-you-up bed between my mum and my brother, I shivered through the night.

The funeral – the first I’d ever been to – was well attended and we got to ride in a special long black car, with seats that faced the front and the back. We were crammed in with my uncle Albert’s widow and son (my never-mentioned cousin) who talked incessantly. Their accents were so broad that I didn’t understand a word, and I remember praying they wouldn’t speak to me, lest I had to keep saying ‘Pardon? Pardon?’ There was a wake following the burial, held at another tiny house in another tiny village. It smelt like chips and egg. The people, too, smelt like chips and egg and they were utterly miserable. I got a sense that their misery wasn’t confined purely to the nature of the occasion. My lasting memory of the whole experience was that in Yorkshire you were always crammed in, people called you ‘duck’ and it smelt like chips and egg. It was grim up North.

Unwilling to follow in his father’s footsteps down the mines, when he was old enough Dad travelled to the South of England where his prospects were considerably brighter. He was determined to escape the bleak reality of mining life as the only future for a young man in Sheffield at the time. Of above average intelligence and having excelled at school, at the age of seventeen he secured an apprenticeship with an international electronics firm and moved to London. By the time he came to be my dad, nearly fifteen years later, the only clue that he wasn’t from the South was when he would lie on the landing outside my and Adam’s shared bedroom and sing, in his round, quite tuneful tenor, the anthem of the Yorkshireman ‘On Ilkley Moor Ba’Tat’. His own broad Yorkshire accent had also, by then, all but disappeared, after years living among plum-mouthed Southerners, save for those occasions when he became angry and his vowels sharpened instantly as if he’d never left t’moors. It was partly because of my father’s Northern roots that Kris chose him and Mum to be my parents. She too was from ‘up North’ and felt some sort of affinity with Dad as a Yorkshireman.

Despite their vastly different backgrounds and just six months after meeting at a coffee evening hosted by mutual friends, Angela and Malcolm marry at a registry office. Both are equally keen to start a family and agree they want four children. But two years into their marriage and now thirty-three, my mother still hasn’t fallen pregnant. After years seeing five different GPs for a referral to a specialist clinic, they eventually follow a friend’s recommendation to see a consultant at Chelsea Women’s Hospital in South-West London. My mother once told me about that first appointment:

The consultant was an elderly man in a dark suit and with a carnation in his buttonhole – very much the old school. He was optimistic that with hormone injections I would get pregnant. These were very painful and I used to hobble round to Harrod’s for a snack afterwards to cheer myself up. There were also lots of other tests I had done, but the doctors still couldn’t make out why I wasn’t getting pregnant; although I seemed to once, but then they said I wasn’t. Dad’s sperm test was fine. I also had had a miscarriage on another occasion. I stuck this out for three years and then this lovely old consultant suggested we consider adoption.

Mum is always wistful and sad when she talks about her not being able to have children. Understandably so, but I’ve always felt that her sadness was greater than her desire to reassure us, Adam and I, that we were enough. Not just enough, but that our becoming her kids was actually sufficient to eradicate, or at least usurp her own disappointment at not bei

ng able to have her own biological children. For a long time, I silently resented her for that. When I was young I would fret about what would happen if by some medical turnaround my mum fell pregnant. What would happen to us? Would we be sent back? Or passed on to yet another family who needed a child to make them feel complete?

The problem was that, although I know I was loved by my parents, there was always the feeling that I was the consolation prize. I was not their first choice. If they had been able to have children, Adam and I would have simply been taken in by some other barren couple who needed to fill an emotional void. We would never have been Adam and Sarah Jane. That troubled me.

Never once in thirty-something years have I ever heard an adoptive parent speak about their desire to adopt being based first and foremost on a need to provide an unwanted child with a family. I’m not suggesting they’re not out there; I’m saying I’ve never met them. The driving force always seems to be to meet a need for that parent. To allow them to fill the child-shaped hole in their lives. For a long time I felt guilt and enormous hurt at not being the child my mother really wanted. It wasn’t even that I wasn’t a true part of her, that she hadn’t carried or breastfed me, or that if things had worked out the way she wanted, I would never have been her daughter. It was that I sensed she felt that had she had a biological daughter, the child would have been more like her, an extension of her. Someone for her to mirror and be mirrored.

As I grew older, particularly in my teens, I would be overwhelmed by the sense that my mother was eternally disappointed by me. I wasn’t the daughter she had really wanted – not as a baby, and certainly not as an angry, confused teenager and young woman fraught with problems. That of course gave me further reason to resent her, I felt so desperately misunderstood and unable to speak about the feelings of sadness, insecurity, abandonment and otherness that haunted me every day. It is a familiar feeling among adoptees. That we must be silent and, above all, constantly grateful.

Killing Karoline

Killing Karoline